Features

Profiles

Back in the U.S.S.R., Presses and Posturing at the Height of the Cold War

December 6, 2016 By Nick Howard

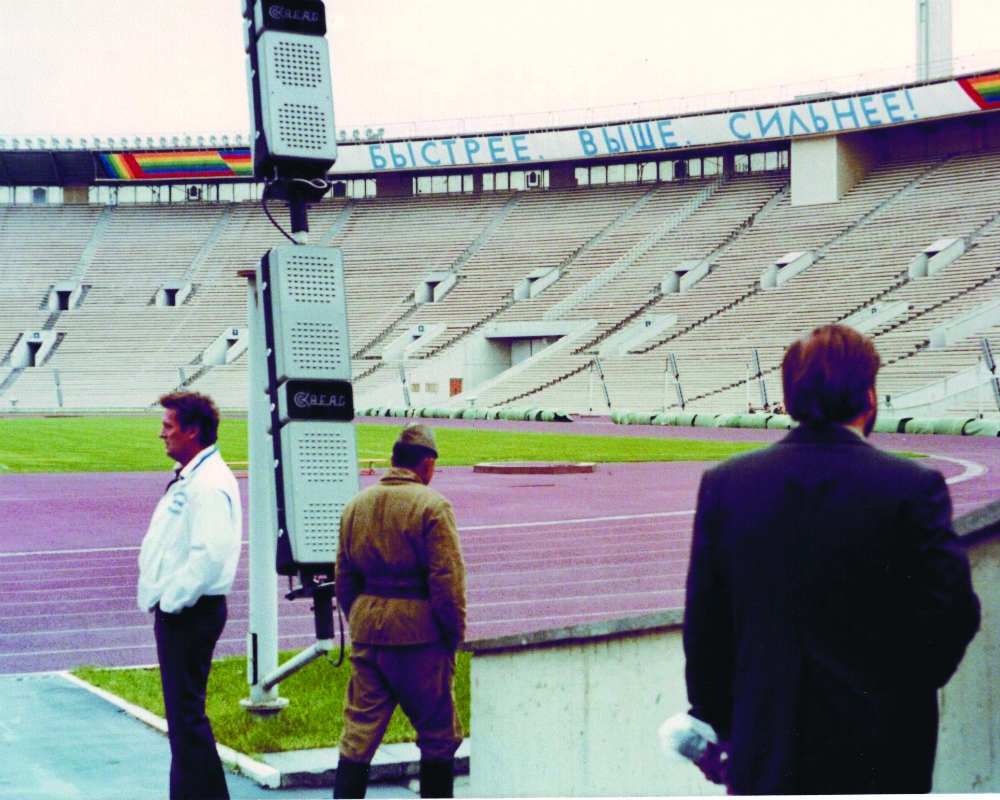

Frank Herrington visiting the Olympic Stadium in Moscow.

Frank Herrington visiting the Olympic Stadium in Moscow. A unique business trip to the Soviet Union, including a look inside the printing operation of the Red Army, at the height of the Cold War leaves a lasting impression.

The world of print has been enriched by many folks from all walks of life who took many different roads to arrive at an industry with seemingly no beginning or end. On a busy mid-week day 36 years ago, a city inspector walked into Frank Herrington’s print shop. “Can you tell me where your designated smoking area is?” asked the inspector. “Wherever I’m standing,” uttered Frank.

This story was often repeated and always with a chuckle. It was a different time. Frank, a lifelong smoker, seemed to have two butts going at the same time. It was never uncommon to see an ashtray with a forgotten cigarette burned to the end with a length of ash. I first met Frank around 1977. He was then a partner in a trade shop but already had a lifetime’s worth of print experience. Born in Hastings, Ontario, to a family with a lot of siblings, Frank had a rough early childhood and found himself and his younger brother, Murray, in an orphanage.

Unlike today, there were few family roots in the printing industry and it was a chance opportunity that Frank found a job at Toronto’s Parr’s Print & Litho in the mid-1960s. Starting with a broom, Frank did all sorts of odd jobs until one day a pressman called in sick and he had the chance to run a varnish job on a Consolidated Jewel. The Jewel was a hefty 30-inch single colour offset press made by ColorMetal in Zurich, Switzerland, but rebranded (as was common in those days), from its Swiss name Juwel to an Americanization Jewel.

Frank was hooked. Especially with offset as he had no interest in letterpress. Like many of his generation, trade schools carried printing courses and taught various disciplines such as typesetting, page assembly, platen press operation, and so on. But for Frank, learning the California job case and composing with type was dumb and tedious when offset offered a better future in printing.

Canadian connections

The ATF Chief 20 was a popular smaller press at the time and soon Frank was running one of these 14 x 20-inch single colours, too. He would run split plates for the record jacket business. This was difficult work, making ready two plates on one cylinder. Next he had the chance to run a Harris LUP two colour. This was a 49-inch press and the big leagues. Over his entire life, Frank preached about the simple intelligent concepts of the Harris press.

Frank also had a short stint working in St. Paul, Minnesota, with Ternes Pin Register. Norm Ternes was instrumental in developing a simple method of installing register pins in plate clamps and also made plate register punches. On his return to Toronto, along with two partners, Frank began manufacturing plate punches and installing systems on all sorts of presses. It’s important to know that even in the early 1970s few offset presses had any kind of pin register.

I once saw him completely re-strip a four-colour cover and print the job on a very old Solna 124 single colour. It was quite amazing to see him manipulate the film, cut the masking sheets, burn the plates and then make numerous adjustments to the press just to get the job out and prove to our customer the press would print.

On another occasion, we had a customer in our shop and Frank was print testing with some plates that the customer had brought. The Harris LXG-FR had Micro flow dampening. What a chore it was to set the dampener, because it was driven by two sets of V-belts. I leaned down to look at the plate docket the customer had brought. Frank, without missing a beat, leaned over and said if I ever pulled out that screen plate he’d kick me into the middle of next week! Frank knew that trying to run a full screen in such conditions would be a disaster.

On yet another occasion, we had sold a printer a Heidelberg KOR single-colour offset press. A few months later that customer had dropped a dampener form into the press and smashed it. Resulting inspections by the Heidelberg agent indicated the press was scrap, so we were able to take it back for parts. After months of this press languishing in our shop, Frank strolled in one day and asked, “Whats up with the press?”

I told him the story and how the press’ owner had said the plate cylinder was bent and it was toast. “But did you check it yourself?” Frank asked. I had not. So we did it together. Much to my surprise the plate cylinder was not bent and we quickly went through it and sold it on to another shop. This lesson was one of the most important Frank would pass on to me.

Our long association proved to be much more than fixing presses and learning common sense. Frank would always challenge you. This trait seems almost extinct today. Over the last 40 years we had many a good mechanic work for us. Some were quite brilliant, others less so. Frank was unique in his ability to speak to owners with confidence while at the same time be a mentor to even the lowest skilled employee. From all walks of life there are folks even today that can share the same sentiments about Frank and how he was the best friend any of them could possibly have.

Frank’s genius was in his confidence. He never let a piece of equipment intimidate him. No matter the complexity or difficulty. Especially with an offset press, Frank’s common sense fundamentals allowed him to almost always disregard the operation manual and use inherent basics to set grippers, adjust bearer pressures or make a feeder run difficult stocks.

Honey, disconnect the phone

Over the next 25 years I would make seven or eight trips to Russia but a visit in 1980, in the midst of the Cold War, was special. For Frank, this was his first visit anywhere out of North America. We traveled aboard an aging Aeroflot Ilyushin Il-62 where the in-flight refreshments consisted of handing out mickeys and chocolates wrapped in tin foil. So here we were in Moscow during two weeks of September 1980. Our goal, to study various printing related equipment manufactured by the Soviet Union and see if we could purchase any of it.

Frank and I had become close friends. He taught me a great deal and I needed him to help me access the viability of the anticipated equipment we would see. We arrived at the scary monolithic Hotel Ukraina near Red Square. A very large haunting and dark place we nicknamed Dracula’s Castle. The Ukraina was a huge place built in a typical Soviet Style in 1953. This was also a foreigner’s Hotel and Russians themselves could not enter without a pass. The room had a black-and-white TV and a radio that was hard wired and couldn’t be turned off. Only the volume worked – there was only one station, too. I recall it was made of Bakelite and had the shape of the Moscow University’s main tower. The radio would chime an eerie tune to signify the top of the hour.

Off we went the next day to the Red Army printing plant. There we were to see the supreme example of the Soviet industrial complex in the POL-54 offset press. This press, a single colour about 74 centimetres (29 inches) was running with two operators (one sitting on a stool at the delivery). To make matters worse the press wasn’t even running offset but rather letterset (dry offset). Frank had a quick look, smiled and whispered, “If that’s all they have we’re in for a rough two weeks.”

Representatives from Techmaschexport (Soviet exporting agency) asked our opinions and I nudged Frank to go take a better look. He’s under the feedboard checking the grippers while all of a sudden the operator hits the run button. This caught Frank’s finger in the press and, as blood dripped from his hand, off he went with a nurse to the infirmary. Shortly after, with a plaster cast the size of an ice-cream cone, in strolled Frank. We never saw the Pol-54 again and apparently no one else did either.

Our days off proved amusing and we had a lot of them. Each place we visited, Frank shook his head. In order to buy something at a store you needed to find what you wanted, get a chit, go to teller to pay, then back with receipt to the first guy. The 1980 Olympics had been held only a few months earlier, so we wandered over to the main outdoor stadium where, to our glee, we found a store that sold potato chips. Nearby was what we would call a fast-food restaurant. We nicknamed it the Bun & Run. They were serving some kind of dish with a flatbread and a white creamy sauce poured over it. Looks good we thought. Pulling out a few Rubles, Frank bought a couple only to find out the sauce was some kind of butter milk. Tasted awful, smelled even worse. The food in the Ukraine was remarkably better than Russia.

We walked each day to Red Square and watched the locals in the GUM department store. We visited a science and technology museum and spent time at the INTOURIST Hotel bar because as foreigners we could get in. But mostly we found ourselves in the main dining area of the Ukraina each night, getting a laugh when we spotted new arrivals trying to figure out that the only drinks were Georgian sweet “Champaign” and Vodka.

We took a flight to the Ukrainian city of Odessa on the Black Sea. There we toured a prepress factory known for platemakers and cameras. It held really nothing of relevance, but we consumed a lot of Vodka during a lunch put on for us. That evening Mr. Ptashkin, our host, insisted we take in a show at the famous Odessa opera. Moments after taking our seats, Frank quickly nodded off. Afterword we walked down to the water on the famous Potemkin Stairs. These sacred steps were constructed in the 1800s and unique because from the top looking down you don’t see any stairs only landings. But on this night somehow, Frank and Ptashkin got into a bet of who could get to the top first. Frank did.

So it’s now after midnight and time to head to the hotel. “Let’s go for a nightcap,” says Frank. There are no night bars in Odessa uttered Ptashkin in a stern voice. “Follow me,” said Frank. Around the back of the hotel, down some steps, knock on a door and – voila – a night bar and with Western liquor to boot. That was Frank, who was somehow a step or two ahead of everyone. Well, we left Frank at the bar and that’s the last I saw of him that night. I was worried in the morning when he didn’t show, having made my way down to the foyer to await our hosts. I was just about to explain Frank’s absence to Ptashkin when he strolled in looking haggard. Best we leave the rest of that story alone.

Soviet presses and the KGB

Once back in Moscow another outing was arranged to visit a major factory in the city of Rybinsk. This city was near a giant reservoir and about 300 kilometers north of Moscow. To get there we had to take the train and also get special permits. The trip involved leaving Moscow in the evening to arrive in the morning. Neither of us actually knew where we were going and looking back it seems nuts to take such a long time to go 300 kilometers. We shared a bunk-bed cabin with the female interpreter and Mr. Ptashkin, separated from the proletariat who had less than stellar accommodations. It seemed every time we awoke coincided with the train stopping, changing direction or in one case stifling smoke in the cabin. Someone had closed a vent for a coal-fired massive tea urn at the rear of the car.

The factory was huge. It still exists today. Back then it also had its own iron foundry. This facility made a wide range of printing equipment from web to sheetfed. A little cold set web press called the POG-60 was actually a licence agreement with West Germany’s MAN and was created to be portable. There were three units and a folder. Two colours one side, one on the back and in a tabloid size. We found this little press amusing because although the Soviet Union had several dailies we never saw anyone reading them – only reading official posted copies of a broadsheet on designated notice boards.

Very large offset and letterpress newspaper webs – all for Coldset newspaper production – were being assembled in the factory. One item of interest was a sheetfed feeder by the name of TIPO, which turned out to be a Planeta design and the Soviets were now building all the feeders that were to be used on these East German presses. Oddly enough, the Soviets failed to use this feeder for their own presses. We were able to view the VOLGA offset press. In a 40-inch size, the VOLGA featured chain transfer from each unit – another dud! We walked past at a brisk pace. But we did have another troubling experience the next day.

There was a special apartment in a workers housing complex. This was reserved for foreign guests. We had a few hours to kill and both of us had brought gum and candies to pass out as gifts. Looking out of the window I noticed some children playing in the late afternoon, so we grabbed our goodies and cameras and went downstairs to hand out the treats. All the kids were excited and we enjoyed making their afternoon.

The next day the Rybinsk general director invited us to a special workers camp on the banks of the lake. Surrounded by woods, this camp consisted of a large house, sauna and outdoor showers. They laid on a feast along with the customary quantities of vodka and toasts. Followed by an obligatory visit to the sauna. A car arrived for us around dusk and we headed back through the woods toward the main road. However, as we cleared the thick trees two black Moskvitch cars blocked our path. Frank and I were ordered to stay in our car while Ptashkin got out to talk to a bunch of guys wearing three quarter length leather trench coats. Moments later a stern looking Ptashkin came back and told us we had been observed taking photographs in a prohibited place the previous day and the “police” insisted that I hand over my camera and film. At first I refused but Frank clearly knew more than I and told me to shut up and give the KGB the damn film. I reluctantly agreed. The KGB developed my film and kept the ones they felt would cause harm to national security.

Funny enough, 14 years later I again found myself at the same factory. By this time the Soviet Union had collapsed and things had changed a great deal. In the huge machine hall, once occupying all types of machine tools, the printing presses were gone and in their place workers were punching out pots and pans. Central planning and subsidies exposed a crumbling infrastructure.

The U.S.S.R trip gave us a lot to laugh about for years after, but the trip ultimately proved to be disappointing. What was very apparent to us was a stubbornness of the Soviets not embracing developments from the outside world. As we later discovered all high-quality printing was not printed in Moscow but in places such as Finland, Austria and Hungary. But that’s possibly because print was not a defense industry and languished because of its apparent unimportance. Odd still considering the Soviet Union, at that time, was the world’s largest producer of books.

I continued to learn many lessons from Frank – both in and out of the printing world. I really miss my good friend in so many ways and I’m not alone. Frank touched a lot of people’s lives and left an indelible mark on all who knew him. We don’t have many in our print industry like Frank anymore. Guys that were strippers, pressman, mechanics and electricians all rolled into one.

I once asked Frank why he had so little respect for authority. In his early days, he had been in the Air Force, trained to use secretive radar equipment. After all the training and being sworn to secrecy, he was walking downtown a few years after leaving the military and saw one of those secret radar units for sale in the window of a surplus store.

Print this page