Features

Chronicle

Opinion

A stroke of genius

But… ink and water don’t mix!

February 13, 2020 By Nick Howard

Fitted to each printing unit, these Dahlgren control stations allow the operator to engage the dampener and control the speed (amount of solution to the plate). All images courtesy of Nick Howard.

Fitted to each printing unit, these Dahlgren control stations allow the operator to engage the dampener and control the speed (amount of solution to the plate). All images courtesy of Nick Howard. Another decade has arrived, and with it, new optimism for a fledgling print industry. Digital inkjet continues to elbow its way into pressrooms around the world, redefining our industry and bringing new hope.

But there was a time when printers focused only on finding ways to produce more for less. Today it’s the opposite — produce less for more money. During the early periods of offset (1906 to 1960), printing press functions hardly changed. Makereadies and wash-ups were long and physically demanding, especially as VLF grew exponentially in the mid-1950s. Three- and sometimes four-man crews manually washed up and pulled dampeners out each night, only to reinstall them the next day.

The offset riddle is still a mystery to most pressmen. The idea that ink and water don’t mix was complex. Water dampening was always segregated and had one job to do — dampen the plate. Ever since the first offset press, dampening was carried out using an absorbent cloth-covered roller. It could hold and retain enough solution and was fed by a ductor roller connected to a roller sitting in a water tray. At the end of each day, these three-rolls-per-unit had to be lifted out of the press, washed (usually in a solution of Pine-Sol), and reinstalled. Not much fun, especially if it was a 77-inch Harris or Miehle.

Woven coverings would have to be changed periodically, and that too was a chore. Still, the biggest flaw was the inability to control the amount of water on the plate precisely. Skill was a prerequisite for the pressman as they balanced the dampener, so a minimal amount of water would not affect the print quality and emulsify the ink. The constant variable in the offset process – going even further back to the very first attempts in 1875 – is the interplay between water and ink. The industry seemed so preoccupied with keeping up with production that few thought of finding a better way — that is, until a young man from Mobile, Ala., did just that.

In 1942, a 20-year-old of Swedish lineage had just signed up to join the U.S. Army. Having previously worked at the U.S. Engineer’s office in Reproduction, Harold Phillip Dahlgren (known as Hal to his friends) first set his eyes upon an offset printing press. While working on a Harris press, Hal searched for a better way. Armed with only three years of high school, he certainly didn’t possess the engineering abilities one would assume to be essential, but that didn’t hold him back. After serving out his military service in the print shop at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, Hal learned enough about offset to get a job with the Harris Intertype Company as a press erector.

“I didn’t know what the answer was, but I did know what it was not.”

By the early 1950s, Hal went freelance so he could put more thought into the problem of eliminating molletons. Science was required – skills he didn’t have – so he set about to simplify the problem. One night in 1954, while brushing his hair, he saw droplets of water on the mirror and in a moment he thought he had seized a solution: A brush roller! Hal moved to Dallas, Texas, built one to fit a web offset press and it worked. A large press manufacturer came calling and agreed to provide annual royalties. Hal was in heaven and quickly took off for a Mexican vacation with thoughts of grandeur. By the time he returned, he realized the brush dampener wasn’t the answer.

Hal described the problem this way: “I didn’t know what the answer was, but I did know what it was not. So I kept thinking.” One day when driving from Dallas to Fort Worth, he recalled something he learned from an old pressman years before. The man ran his finger over an ink form roller to check the ink-water balance. “But… ink and water don’t mix! That can’t be true!” Hal turned the car around and headed back to Dallas, and by the time he got home, he had figured out what he needed to do. The second attempt became known as the Sponge machine, because a sponge roller sat in a tray and supplied water to a newly developed hydrophilic chrome roller and then to the inker form. Although the idea worked and Hal sold quite a few, a sponge was not the answer. However, the concept directs Hal into a new territory that would eventually lead to a fantastic breakthrough — altering the speed of the chrome roller.

Who knew that phosphoric acid made chromium hydrophilic?

The Dahlgren Manufacturing Company was off and running, or was it? Not so fast. There was still a variable and it was related to press speeds. The faster the press ran, the fewer problems. But slower (and at that time, any high-quality work was run at reduced speeds), and water streaks showed up on the plate. How could that be resolved?

This time, the answer came to Hal in a martini glass. “One evening, while racking my brain about those water streaks, I fixed a martini and sat down, and [was] rolling the glass in my hand. I was trying to think out a solution when I noticed the behaviour of the moisture right at the level of the martini. It was always working. Little things were running up and down. It occurred to me that alcohol mixes with water, and maybe that’s a good thing. Alcohol evaporates [and] leaves no residue.” Isopropyl alcohol (IPA) would solve a host of problems and also reduce the surface tension and amount of water needed. The old pressman’s catchphrase – “alcohol makes water wetter” – would live on until IPA was outlawed in the early 2000s. The addition of alcohol would also mark the start of refrigeration and recirculators.

“Thank God, the waitress did not take off the empty cans.”

Dahlgren had a workable dampener, one that was so simple to operate (only three rollers) and it provided instant ink-water balance and had virtually no maintenance. Foremost, there were no molleton covers to change and ink emulsification became a problem of the past. But a final hurdle soon appeared. It’s important to note that by 1960, the Dahlgren Company had virtually no assets, no manufacturing and only a few loyal employees. The debt was like a dark cloud hanging over Hal’s head. Only an offset printer would have seen the excitement building. For everyone else, it’s as if Dahlgren was discussing the merits of wall thicknesses on cast iron pipe — dull, to say the least.

The final hurdle was only unmasked after Dahlgren won a few orders to go on 60- and 77-inch presses. These large formats magnified the problem of rollers being too wet in the middle and too dry at the ends. Hal recalls the answer: “One afternoon in 1961 in a Mexican restaurant, I was drinking a can of beer, trying to figure out what would solve the problem. I finished the can and ordered another. I poured it into a glass. Thank God, the waitress did not take off the empty cans. I picked them up and rolled them together, twisting them a bit and then, bingo! There it was. The skew device — a metering roller adjustment that would let me positively control the moisture all across the plate.”

With a perfected dampener, it would seem that every printer would be knocking on Hal’s door, but few printers grasped the significance of the invention. The ones who did held it in secret, not wanting competitors to get the same edge. By 1962, the Dahlgren Company was at nearly US$250,000 (US$2 million today) in the red. Hal had to demand 50-percent cash upfront on new orders, and if a printer checked Dahlgren’s credit rating, it usually backed off assuming Dahlgren would be out of business in the next 72 hours. Plowing on a seemingly even steeper incline, Hal sought out an investor. This guy, who had made his money in trucking, hired the Arthur D. Little firm to survey the litho industry with an emphasis on plants using early Dahlgren models. The results were encouraging. Users of early dampeners said they had bugs in them. “Why don’t you take them off?” “They still work better than the conventional system,” they said. The investor made Hal a $1-million offer, and he thought about it before declining — he would go it alone. In January 1963, Dahlgren changed its sales pitch. Now Dahlgren offered to install its dampeners for nothing down and if the printer liked them excellent, if not, Dahlgren would take them off and reinstall the old molletons. “Once we put them in, the Dampeners sold themselves,” Hal said.

Today, every offset press uses Hal’s brainchild invention

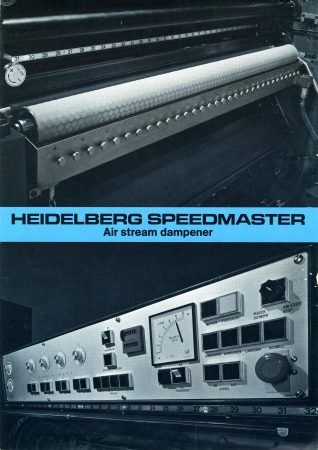

Soon after, Hal – who held patents on his designs, signed agreements for licencing with Harris and Miehle. In Miehle’s case, a licence-royalty agreement that allowed Miehle to adopt the technology into its Miehlematic dampener. Because Miehle also represented Roland (now manroland), Roland entered a similar royalty agreement when it designed the Rolandmatic dampener. Some companies refused. Heidelberg, steadfastly defiant, warned off buyers of new presses, citing a potential loss of warranties and the negative impact of a loss of the first ink form, an issue Dahlgren would fight for decades. When it became apparent to the Germans that Dahlgren’s continuous flow dampeners were far superior, Heidelberg tried a workaround designing the ill-fated Air Stream Dampener in the late 1970s. When that failed, Heidelberg set about to develop Alcolor, first in 1979 (which also failed), then finally in 1982 the highly successful Alcolor II. Heidelberg would design a crowned rubber metering roller to counter the Dahlgren skew feature. Every press – and I mean every press – today uses Dahlgren’s technology.

Dahlgrens appeared everywhere in North America, but was very slow to catch on in Europe. Often the Swedish name Dahlgren was mashed to read Dahlgreen. Japan embraced the Dahlgren concept, and Komori soon had its version – Komorimatic on Lithrones and Sprints – but again with a necessary workaround reverse-nip to shield Komori from patent violations.

Having to give up the first ink form roller continued as an irritant for Hal. In 1977, his brother Harvey left the company to begin manufacturing his own version of the dampener, this time leaving the first ink form alone. Epic Products continues to this day. Epic also offered another revolutionary design, thought up by a California printer, then sold to Baldwin: The Delta [effect] dampener. Now commonplace, the altering of the form roller speed (7 percent slower than the ink and plate) reduced hickies and ghosting.

Ill-fated gambles, along with an ever-shrinking customer base, would prove to be insurmountable for Hal. First, an anti-ghosting inker retrofit, then owning an ink company, and a new radically designed Hustler offset press couldn’t return the magic that made Hal a household name. The concept Hustler did have some revolutionary features. It was a tandem perfector and printed four-over-four without turning the sheet. This design would be emulated by Akiyama then Komori 20 years into the future. However, Dahlgren tried to use only a chain with grippers to take the sheet from feeder to delivery, and that failed utterly. If you’ve ever seen a Bobst Autovariable, it worked the same way. Besides, Harvey’s Epic Products and most press manufacturers’ versions were nibbling away at a shrinking retrofit dampener business.

Eventually, Hal left the business, and ownership changed hands several times before disappearing from view. Montrealer Paul Belair purchased the business in the 1990s, rebranding under the name MMT. MMT now does business in Georgia under a new umbrella name, MMT Sales & Design, but the Dahlgren dampener ran its course.

For anyone running a press in the 1970s and 1980s, you already know what a revelation Hal created. For those young enough to start running presses in the last 20 years, you probably have no idea. Rapid inventions such as closed-loop colour control, automatic plate loading, in-press density and presetting features all came about by a natural inclination to use exciting new technologies, devices or software. But what Dahlgren did was more profound than that. Hal didn’t have all these technological tools at hand; he didn’t even have an education. What he did have was an idea and a dogged determination to succeed.

Improvements to the offset process mostly came about as technology improved — think electronics. Hal had to borrow a press to continuously refine his invention. He didn’t have a lab full of equipment and an army of engineers at his fingertips. There was nothing ‘natural’ about the Dahlgren theory as just about every rule of common sense was broken. As long as there is an offset press, his genius is at work. Makereadies and paper waste plunged with Dahlgrens. In 1985, Hal died at the age of 63, but what he left our industry lives and prospers to this day, and for however long, the offset press remains an integral part of print. I believe the Dahlgren dampener was the most profound improvement ever to be applied to offset.

Nick Howard, a partner in Howard Graphic Equipment and Howard Iron Works, is a printing historian, consultant and Certified Appraiser of capital equipment. nick@howardgraphicequipment.com

This article was originally published in the January/February 2020 issue of PrintAction, now available online.

Print this page