Features

Chronicle

Opinion

Not everything turns to gold

Analyzing Heidelberg’s decision to end its VLF collaboration with Fujifilm

October 2, 2020 By Nick Howard

Heidelberg’s Rotaspeed V1 never even made it out of the factory.

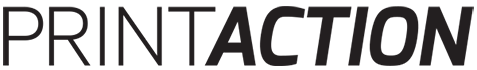

Heidelberg’s Rotaspeed V1 never even made it out of the factory. This past March, amid a worldwide pandemic, news from the world’s largest printing press manufacturer may have caught some in the industry by surprise. Heidelberg’s much-touted collaboration with Fujifilm, developing the world’s first inkjet 40-inch press, was ending. Adding to the astounding news, Heidelberg would also cease producing their VLF (very large format) presses.

The Primefire 106 came to me in puzzlement, but VLF not so. The moment I laid eyes on the launch press at Drupa 2008, I could see one obvious shortcoming. The press was too monstrously over-built. It seemed unimaginable that in such a small yet exclusive sector, Heidelberg would ever sell enough given the magnificence of the design. Too big and too expensive: customers also had to essentially engineer massive foundations, with Heidelberg factory engineers and bespoke erecting teams on-site to put the presses together. In 1972 Heidelberg made a similar decision building a massive size six (56 inch) Rotaspeed V1 that never even made it out of the factory. Was this a scene out of the movie Groundhog Day? Didn’t that earlier lesson suggest something?

Koenig & Bauer and manroland also build large format but not to the overblown extent of Heidelberg. A Rapida 162A can be quickly dismantled to fit regular shipping containers except for the feeder and delivery. Rigging requires nothing particularly special and installation very quick. In Heidelberg’s case, special rail systems, super-size crates, and associated freight cost just added a higher expenditure to an already pricey press.

Commercial print buyers were scarce

As it turned out, these monsters were absolute winners when it came to uptime and productive running speeds. Shortly after the 2008 launch, a perfecting option was added, but that horse had already bolted with a severe reduction of four-over-four commercial and book work. Printers were dealing with shorter run lengths and preferred smaller B1 (forty-inch) presses. The few web-to-print wholesalers, some even installing the roll-to-sheet CutStar option, were scarce. Folding-carton was a much different story as the Speedmaster VLFs eclipsed what had previously been possible in terms of throughput and make-readies while stealing the crown from the other two manufacturers. No doubt, a massive sigh of relief emanated from Würzburg and Offenbach when they read the news.

The co-developed Primefire 106 struggled to gain sales, mainly because of the sale price. Still, everyone knew digital, and most assuredly, inkjet would soon be the technology that would displace the Offset method. However, the shock of termination amplified in our current climate, where no one can afford to wait for the rest of the industry to arrive. These two changes appear devastating, but in reality, machine tools and real estate are liquid assets. In the case of the Primefire 106, it was mostly composed of an existing Speedmaster 106 with only a specially designed imaging unit, and a console shoved into the delivery. As Heidelberg is legendary for its spare parts and service, these will likely continue well past the end of natural life.

So, it seems the printing industry will not spend millions of dollars on technology that runs at speeds of the 1950s. Price is an obstacle that every potential 40-inch seller, including Landa and Komori, may face.

The joint venture with Fujifilm is the second go Heidelberg has had with digital. The first ended in tears back in 2004 when Heidelberg ended their venture with Kodak. At that time – as it is today- everyone knew the industry was changing, and sooner or later, printers would convert to some version of the digital method. Trouble was, not many were willing to write checks. Time and massive write-downs forced Heidelberg to react the same in both cases.

The life of machine builders, and that includes our printing machine manufacturers, are continuously fraught with whether or not some new device or design will be a winner. Numerous examples exist of machine concepts that came out of departments with shelves groaning under the weight of drawings, only to belly flop. Every builder has these miss-fires during their lifetimes. I’m sure Komori would like to re-think the decision to build a sizeable perfect binder without a gatherer back in the mid-1970s, but they didn’t. Neither did Koenig & Bauer with their chain-transfer bright yellow SRO presses. Disturbingly this time the (PrimeFire 106 and VLF) problem was not performance, but financial.

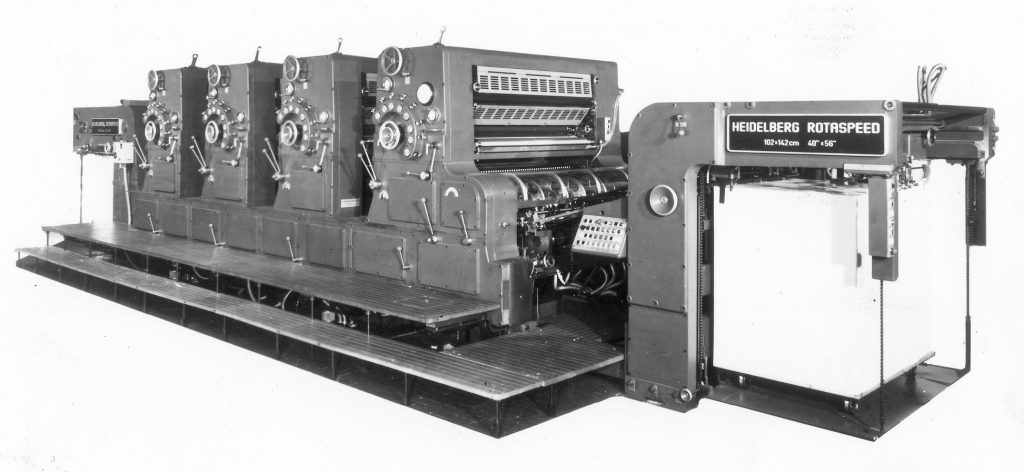

And so it was, back in 1967, when Heidelberg thought they were on to something that could breathe new life into letterpress. The mid-1960s were inundated with print—notably books. Newfound technology in perfect-binding solved the problems of having to use animal glue and side nailing to keep the increasingly popular paperback books from falling apart. Everyone it seemed was installing perfect binders with the new “Hotmelt” adhesives, and book prices were coming down. To produce these books ideally meant perfecting (printing both sides in a single pass). There were not many sheetfed choices in those days, unless printers purchased a dedicated offset press such as the Crabtree SP56 or similar models made by MAN and Marinoni or many other blanket-blanket presses, three of which would be soon to arrive from Japanese builders Komori, Akiyama and Mitsubishi. Of course, first-generation “convertible” perfecting with Miller TP-38 or TP-54 presses was also popular.

“Two Waldorf salads, please!”

Heidelberg’s perfecting press was able to turn out pages at a reasonable speed of 5,500 impressions per hour using inexpensive relief plates.

Heidelberg wanted to catch the wave of new letterpress plate technologies that rapidly appeared with both DuPont’s Dycril and Germany’s BASF branded Nyloprint plates. Both were metal-backed, about 0.8 mm thick and used not only for letterpress but with the film flipped on exposure for right-reading, ideal for Dry-offset on an offset press with requisite ground plate cylinder. Besides, Heidelberg wasn’t entirely new to this game, and especially with DuPont’s efforts in America, Dry Offset was also gaining popularity for books and other simple monochrome work. In 1962, Heidelberg designed a small two-colour (non-perfecting rotary press), the 40 x 57cm KRZ. Now, why not design a much larger format, say in the SRA1 (640 x 900mm) sheet size that could accommodate A4 sixteen-page work, perfected in one pass?

During May 1988, I was visiting the Heidelberg rebuilding center, just near the main Wiesloch factory, in the town of Waldorf. Yes, the same Waldorf that would lend its name to the salad. This shop was magic. Speedmasters and S-Offsets were rebuilt entirely along with all sorts of letterpresses, from the T-Platen to SBDZ. Finished machines looked like new! Packed away at the rear storage area was a press I’d only read about in a Heidelberg catalog. My eyes were drawn to it in fascination. The press was a model SRDW. The designation is loosely translated as fast-rotary-perfecting-press.

During our years in business, there are but only two models, excluding the VLF and Primefire 106, we never bought and sold. The first was a very short-lived KSL, which was a flat-bed letterpress with an offset upper unit. The second was the SRD series. We have sold everything else: from the iconic little T-platen to the Speedmaster 106. Initially launched at Drupa 1967, the press came in only the SRA1 size but in three variants: SRDE-single color, SRDZ-two-color, and SRDW-two color perfector.

“We have built the best performing technology. What could possibly go wrong?”

At the time, I just looked at it, amused. Why in 1988 would anyone buy such a thing? Hadn’t the industry moved on from letterpress? Furthermore, why on earth would Heidelberg even have such a fossil ready to be rebuilt? But as time went on and we started to think about building a museum, I remembered that SRDW and started to envisage having such a unique piece of history: we just had to have one of these. As it turns out, Heidelberg made very few: our research indicates less than 126 in all three variants were made between 1967 and 1973 when it was quietly put to rest. Finally, after years of searching, our museum found one parked in a Berlin book bindery. The company was using the SRDW to die-cut with foil dies. Diecutting was never in the scope of work for this press, but it must have done the job judging by all the waste we had to clean out. The upper first unit has an extra cylinder that carries the sheet to be printed, and then back to the main double-size impression cylinder where the bottom unit prints the backside. Some type of anti-marking tympan was used – probably 3M’s Spherekote, which was invented in 1947.

Our press was manufactured in 1969 and would have had the original Spiess BX stream feeder. But the Spiess was upgraded to the newly developed Heidelberg head (invented in 1969 by Arno Wirz). The press was originally black but had been repainted grey, which became Heidelberg’s new livery in 1972. Could it be that the press I saw 32 years ago in Germany is our press after a makeover? We may never know—but one thing is for sure, it is a beautifully designed piece of equipment. From the user-friendly feeder to a swing-arm in-feed with pull side-guide, the SRDW used some existing technology but also was responsible for designs that would be used later on with the S-Offset: delivery grippers being a good example. The way it perfects is the most fascinating part for me. Anyone who has run older Heidelberg rotaries can easily navigate through the SRDW and a key argument of why Heidelberg has always been considered the pressman’s press. Now, after a full restoration, our SRDW – probably the most unique machine Heidelberg ever made, is on display and soon to be printing again at the museum.

Heidelberg certainly had a good idea back in 1967. They designed a perfecting press that could pound out pages at a reasonable speed of 5,500 impressions per hour using inexpensive relief plates. Heidelberg foresaw the need for perfecting and the public’s appetite for pocketbooks. What they couldn’t know was the speed at which Offset would eclipse letterpress. And just as they did recently with Primefire 106 and VLF models that offered little return or were too expensive to build, they hit the brakes on the SRD series and moved on. Others had similar harsh decisions to make. Koenig & Bauer spent years pushing their Rotafolio version of relief printing before they too put a stop to it. Dry Offset, or Letterset as it’s called in Germany, lives on today, especially for metal decorating and label printing. But for book work and any other type of B/W printing, even the offset press struggles to maintain a hold as most of this work is slowly vanishing.

The SRDW is the story of machine development, and every single press manufacturer has a book full of missed or unprofitable equipment that either because it was not the right time, or the market wasn’t willing to buy enough, was forced into painful decisions. In 2020 no one, including Heidelberg, can afford to wait it out. Today this is our reality. Heidelberg made the right call. Meanwhile, for anyone interested in the rich history of printing presses, we have saved an extraordinary piece of Heidelberg engineering you may never see anywhere else.

NICK HOWARD, a partner in Howard Graphic Equipment and Howard Iron Works, is a printing historian, consultant and Certified Appraiser of capital equipment.

nick@howardgraphicequipment.com

This article was originally published in the June 2020 issue of PrintAction.

Print this page