Features

Chronicle

Opinion

Cornering the market

Offset’s early attempts at mercantilism

March 26, 2021 By Nick Howard

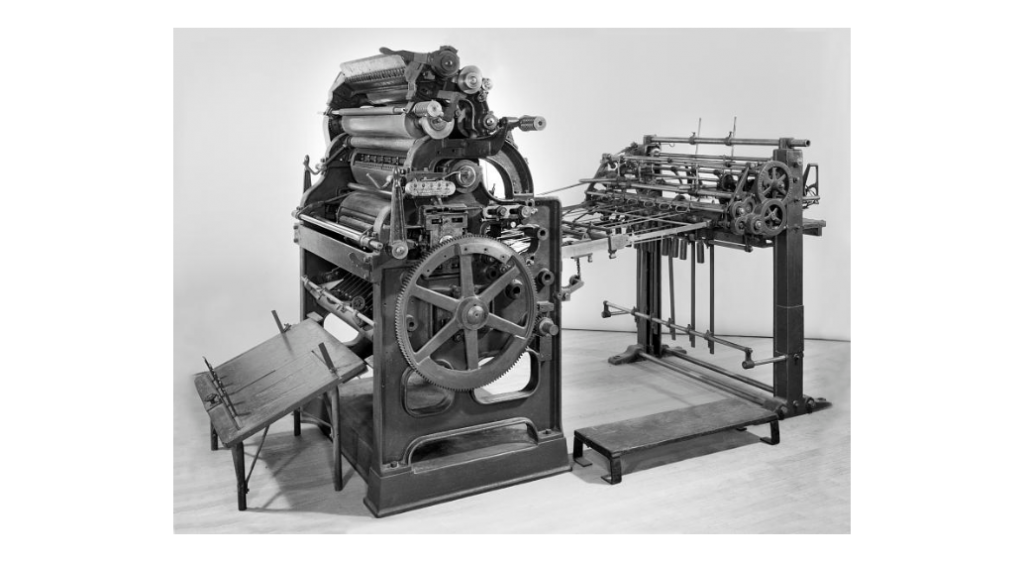

The original Rubel offset press.

PHOTO: DIVISION OF WORK AND INDUSTRY, NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION.

The original Rubel offset press.

PHOTO: DIVISION OF WORK AND INDUSTRY, NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION. Ira Washington Rubel was a born salesman; he could spot a winner with just a glance. Having passed the bar in Chicago, Rubel ran his own print shop in Nutley, NJ. The business was booming, and Rubel ran several Direct Rotary Litho presses, which used zinc litho plates directly transferred to paper. Rubel also owned a small paper mill producing cheap sulfate paper used to gang-run bank deposit slips on large sheets, thereby destroying the competition. One day a sheet was miss-fed, and to everyone’s surprise, the wrong-reading image had transferred to the cylinder tympan with more superb quality than printing directly to paper. This would become the Eureka! moment that would change everything. Rubel studied the tympan in greater detail, and as if he was looking through the form, he realized something magical just happened. Rubel knew what he needed to do: design a new printing press using a new technique with three rotary cylinders. The year was 1904.

Only the Rubel discovery wasn’t so new. Since Austrian/German Alois Senefelder’s accidental discovery of lithography in 1800, lithography using Bavarian limestone had been discovered, yet developed very slowly. It wasn’t until 1821 when Barnett & Doolittle opened shop in the U.S. that the Americas even had a practical stone printer. The real Eureka! moment actually arrived in 1875, when Englishman Robert Barclay invented what would be true offset. Barclay was a metal decorator, and his new machine featured an extra cylinder with specially treated cardboard as the transfer medium. Nobody ever thought to attempt printing on paper other than tin printing (printing on steel sheets). At least, until the little mishap in New Jersey at Rubel’s Litho-Print Company 30 years later.

Rubel got busy. He hired an engineer who designed a single-colour 36” with three cylinders (plate, blanket and impression) of the same diameter. A suction pile feeder supplied by the E.C. Fuller Co. of New York was added. Word spread throughout the United States that a newfangled contraption had been invented that just might make letterpress redundant.

The Jenison C. Hall printing company of Providence, RI had expanded and opened up an office in San Francisco in 1887. But J.C. Hall, a big player in producing bank stationery, farmed out all their lithographing to New York’s Schmolze & Hildenbrand printers. J.C. Hall’s west coast plant would soon be renamed the Union Litho Company. Luckily, the Spanish-American War proved a boon to Hall, since they were in a select group of seven contractors appointed in 1898 for imprinting stamps on checks. In 1905, Hall’s owner, Bert Hubbard, contacted Rubel and requested a visit to see the press as he heard whisperings about the Rubel machine.

Cartels seldom work for long

Nick Howard took this photo of the Rubel offset press at the Smithsonian’s American History Museum in 1988.

PHOTO: NICK HOWARD

Under a cloud of secrecy, Rubel agreed, and the two met in the confines of the Eastern Lithoprint Co shop in New York City. Until then, nobody from the east coast was allowed to see the new machine. Hall’s plant in San Francisco apparently wasn’t a problem, and at this meeting, Rubel agreed to sell J.C. Hall two offset presses for a sum of $11,000. ($325,000 today). Considering a typical flatbed letterpress cylinder was selling for $1,500, one can sense the excitement of owning a true offset press. One press was delivered just as the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 struck northern California, but luckily, the press was still sitting at an Oakland transport depot and was undamaged. Once installed, the press took months to get going, and Ira Rubel’s brother, a mechanic, was put in charge of the installation. This press is now at the Smithsonian Museum.

The same year, Ira Rubel announced that he was forming a joint venture with a Chicago printer, Ike Sherwood, and the new entity would be called the Sherbel Syndicate. Ike Sherwood had many reasons why he didn’t want any other printer in Chicago to get the offset advantage over him: mainly, Charles Goes of the highly-respected Goes Lithographing Co. As partners, Rubel and Sherwood laid a plan and announced they would grant only eleven printers the “opportunity” to purchase the Sherbel offset press.

Oddly, Rubel attempted to register a U.S. patent for his invention, but was stifled. The Patent Office ruled that “offset” was already an accepted art since the metal decorating industry (printing on metal) had been using the technology for at least 30 years.

Initially, the two partners would be introduced to machine builder Andrew Kellogg. Kellogg manufactured his press in New Hampshire but soon left the partnership, leaving Rubel and Sherwood to fend for themselves. Money was tight and the iron casting foundry would not release any materials until paid in full. The syndicate was in serious trouble.

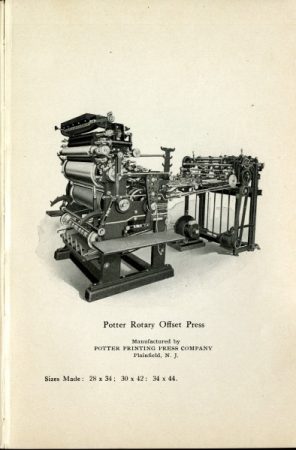

Sherwood went to the Premier-Potter Ptg Press Co. of Plainfield, New Jersey, for assistance, and Potter agreed to build the Rubel press going forward. Sherwood’s partnership with Potter ended the syndicate, and in 1906, Rubel found himself in England. Although his many stories have managed to live on, one trait stands out: Rubel, with his derby hat, was a born salesman and a hustler; he just couldn’t run a machinery enterprise.

Boy blunder heads for greener pastures

In England, Rubel contacted the well-respected printing machine builder Waite & Saville of Otley. The two worked a deal for the Rubel to be manufactured, but Rubel was still contacting other manufacturers. The George Mann Co. in Leeds came into possession of various sketches and print samples left at Rubel’s hotel and quickly decided they too would manufacture a press of their own design. Rubel would die virtually penniless of a stroke while still in England in 1908.

Back in the United States, Potter Ptg Press Co. was busy working the kinks out of the original Rubel press and stepped up production to become the first offset press manufacturer in the world. Ripples of interest turned into torrents when the Harris Automatic Press Co. modified a 30” rotary letterpress (the S4) and turned it into an offset (S4L). Several others, including the Andrew H. Kellogg Co., who was an early participant with Rubel, the Hall Printing Press Co., Walter Scott & Co., and the R. Hoe & Co. entered the fray with various models of their own. Hoe and Scott both pushed hand-feed presses, while the rest had aligned with some of the suction feeder firms such as Fuller and Dexter.

As we now know, Harris received the most significant life changing benefit of offset, but Potter was not far behind. In the United Kingdom, Potter held a premier position in offset presses for over 19 years, before finally being engulfed by Harris in 1927.

This short review of the dawn of the offset press has been repeated many times. However, what has not been discussed are the mistakes both Rubel and Sherwood made in attempting to “corner the market” on a blazing new technology. Provided that Rubel was able to finagle a U.S. patent, would he have been able to decide who he would sell to? The answer is absolutely not. Somehow any new technology will find its way to market: either through the inventor or by reverse-engineering. The Sherbel Syndicate fiasco is still a lesson for today, especially in world trade, where threats of duties and restrictions negatively impact all human beings.

In this year of remarkable events, current offset manufacturers have either learned from Sherbel or not. I think for various reasons, they have. Print technology’s future is not going to be offset, but imminently starting to look a lot like the hybrid offset/digital processes are being intertwined. Koenig & Bauer is putting resources into new platforms. The Delta SPC 130 FlexLine Automatic is a joint venture with the Italian inkjet company Durst. Although specified for corrugated, the press combines tried and tested elements of K & B’s sheet handling and coating technology with Durst’s inkjet platform. The VariJet 106 is a further example, for paper and carton, using Fujifilm Dimatrix Samba inkjet heads. Komori decided years ago that ignoring the higher-tech digital manufacturers might be a mistake. Komori’s partnership with Konica Minolta for a smaller inkjet press, and more recent association with the Israeli firm Landa Digital, sends the same message. At one time, offset manufacturers turned up their noses at the smaller toner and inkjet suppliers, as if these digital guys were annoying, but never a threat. Today the tables are turned, and offset presses are starting to embrace digital.

In this year of remarkable events, current offset manufacturers have either learned from Sherbel or not. I think for various reasons, they have. Print technology’s future is not going to be offset, but imminently starting to look a lot like the hybrid offset/digital processes are being intertwined. Koenig & Bauer is putting resources into new platforms. The Delta SPC 130 FlexLine Automatic is a joint venture with the Italian inkjet company Durst. Although specified for corrugated, the press combines tried and tested elements of K & B’s sheet handling and coating technology with Durst’s inkjet platform. The VariJet 106 is a further example, for paper and carton, using Fujifilm Dimatrix Samba inkjet heads. Komori decided years ago that ignoring the higher-tech digital manufacturers might be a mistake. Komori’s partnership with Konica Minolta for a smaller inkjet press, and more recent association with the Israeli firm Landa Digital, sends the same message. At one time, offset manufacturers turned up their noses at the smaller toner and inkjet suppliers, as if these digital guys were annoying, but never a threat. Today the tables are turned, and offset presses are starting to embrace digital.

Starting from scratch has a massive cost if anyone not already in the game wants to attempt a new inkjet alternative. The only ones that can do this are companies that have already spent the R & D money and have the resources, engineers and scientists already deployed.

The lessons of controlling production and deciding what a printer gets to buy are long gone. The printing industry has very little time to think long-term. The Sherbel disaster, had it played out differently, would have left more of us remembering Ira W. Rubel’s name.

Nick Howard, a partner in Howard Graphic Equipment and Howard Iron Works, is a printing historian, consultant and Certified Appraiser of capital equipment. nick@howardgraphicequipment.com.

This article was originally published in the December 2020 issue of PrintAction.

Print this page