Features

Chronicle

Opinion

When the next big thing … isn’t

The long-forgotten zinco-aluminum press

April 16, 2021 By Nick Howard

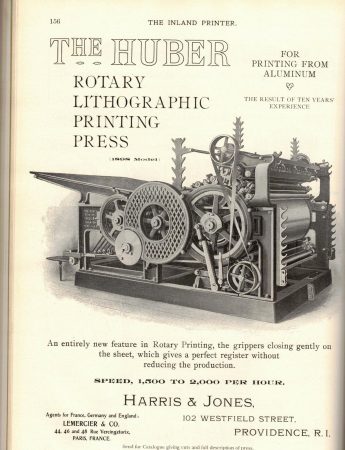

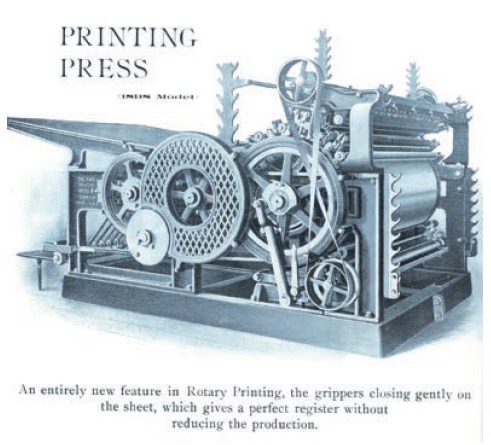

Huber Direct Lithography press from 1898. Photos courtesy Nick Howard.

Huber Direct Lithography press from 1898. Photos courtesy Nick Howard. Whatever happened to beaver pelt hats and mink coats? The former went out of style in the early 20th century, while the latter is perilously close to the same fate. If there is a “want,” then someone will source and capitalize on materials needed to satisfy it. Once a society has moved on, complete industries are often wiped out if they didn’t pay heed to the prevailing winds of change.

In one notable case, when a rabbit pelt seller in France learned that his largest customer, Haloid/Xerox, found a new man-made material to replace fur wipers for their 714 photocopiers, he committed suicide.

Perhaps the next behemoth to fall will be “Big Oil.” Radical new battery technologies will empower more fuel guzzlers to use the grid and thereby reduce the oil demand. The reduction of crude will slowly trickle down to petrochemical refineries and result in price increases for the host of oil-based by-products humans desperately need.

During the printing industry’s existence, there are many examples of technologies that were supposed to solve problems and failed. During the early 1800s, printers were increasingly on the lookout for a new process or machine that would increase print quality and raise production levels.

My good friend, Frank Herrington, once opined that a machine’s mechanical concepts can be simple to understand. “Motion can only travel up and down, back and forth or around in circles,” he said.

Printers knew this to be true, as did anyone attempting to invent or improve a mechanical device, and printing presses were certainly clumsy devices that needed all the help they could get. A circular motion was key to increased speeds and when the first Gravure attempt was identified in 1852 England, progress on a new technology began.

The radical new process of Gravure

Nicephore Niepce and Fox Talbot hand-engraved copper plates for a radically new process which even today is still in use. Gravure (or Tiefdruck in German) is an Intaglio process. The history of Intaglio dates back centuries before Talbot and still commands a percentage of print today. One only needs to look at paper money or a stock certificate to see and feel the difference. In 1852, Talbot wasn’t attempting another “engraving,” but rather a new way to utilize the wondrous invention of photography.

With film developments beginning in 1839, Gravure printing could increase reproduction quality. It wasn’t until Mungo Ponton discovered a paper soaked in bichromate of potassium that he realized he had made the paper light-sensitive, thus leading to another compound, bichromated gelatine. This last bit would lead to Karl Klic, a Czech, to invent the Carbon Tissue Resist and usher in the real beginnings of applicable Photogravure in 1877. This process utilized the gelatine applied to the carbon sheet, which is impervious to the acids used to etch the image on a plate or later a roll (Rotogravure). The results were mind-blowing. For the first time, images, such as a halftone, could be printed as if they were the original photograph. A long-plagued problem for printers was in replicating the wide tonal values in letterpress. Film improved tones and Gravure was now thought to be important and would be continually improved to exploit the opportunity.

Letterpress soon discovered a use for film in the discovery and development of “electros.” Electros are usually copper plates that would take the bichromated gelatine discovery for their gain and produce much finer reproductions than lead or hand-carved woodcuts. Although initially a hopeful new technology, Gravure faced the headwinds of Letterpress for decades to come. As hard as they tried, Letterpress Printers would never reach the quality of Gravure, and ironically, Gravure found new markets.

Well into the 20th century, Gravure was (and still is) used for everything from long-run magazines to packaging. The trouble was, the process was incredibly costly. The agony of preparing a cylinder or plate required hours of tedious work by specialists. Complete chromium plating lines and spindle grinders were only but a few of the expensive pieces of auxiliary equipment needed. Then there were machine-room costs to prevent explosions and fires. The flammable solvents used in the ink were not only toxic, but easily ignitable. Large Rotogravure plants would require expensive fire-abatement systems including carbon dioxide, stored in bottles, and made to release in the event of a fire breaking out. If the bell rang and you were slow, chances were, you’d be carted out of the factory boots first.

The Direct-Lithographic or Zinco press

Gravure would also harm Planography (Lithography) during the late 19th century. Stone printing had been the best way to reproduce fine art and anything with shading or half-tones, and although agonizingly slow, drew clients who insisted on only the finest reproductions. Gravure had been gnawing away at Lithography because it excelled at everything Lithography was good at. With massive infrastructure costs, Gravure printing was also the most expensive. What to do?

The old stone-men figured that if they could eliminate Solenhofen limestone in favor of a thin metal plate, they could alter the landscape tremendously. Zinc plates were first chosen as zinc could be rolled down to a thin sheet of say 0.024 inches and made sensitive with a series of processes similar to Gravure. This attempt grew legs and by the 1890s was being used sporadically in Europe and America.

Initially, a modified letterpress was chosen, but talk soon turned to devise a “special machine” that didn’t have a back-and-forth bed, but two rotary cylinders: a plate cylinder and an impression cylinder. If you took a modern offset press, removed the blanket cylinder, and placed the plate cylinder (with ink and dampener) in its place, you have a Direct-Lithographic, or Zinco press. The terms Zinco-Lithography and early in the 20th century, Aluminographic-Lithography (the first use of aluminum) would enter our vocabulary. Dozens of press manufacturers rushed Zinco presses to the market and clambered to take advantage of the faltering stone industry. These rotary presses didn’t suffer from the old ways of back-and-forth letterpress, plus the plates were cheaper than stone.

New technology was born and ready to take over the entire industry. Only, that’s not what happened: zinc and aluminum plate processing was fickle. Add the expense of large cameras, platemakers, graining machines, and skilled “touch-up” artists, and you can imagine the road to modernity was fraught with potholes. Direct-Lithography saw its peak between 1898 and 1904, when Ira Rubel re-discovered the long-forgotten Offset principle. Its time in the sun was over, not because of niggling plate problems, but because the print quality was not great. Manufacturers, who must have poured fortunes into machinery, found no buyers and even today, I have never seen a surviving Zinco or aluminum press. Just as quickly as it appeared, Direct-Lithography was gone to history.

Gravure, of course, didn’t disappear and went on to be dominant well into the 1990s, only losing much of its magazine work to the surging Web Offset market. Recently, the British press reported that OK! and Hello! magazines had changed printers and would no longer print Gravure. In the 1980s, Playboy and National Geographic were just some of the bigger names that heralded a massive switch to Web Offset. But Gravure held onto labels, packaging and various important elements of print. Technology advanced accordingly to reduce the costs of cylinder preparation, with sleeves often used. Gravure, through its spinoff Aniline (flexo) even gave Offset printers the technology to incorporate a doctor blade and screen-roller in their coating units. If you have a TRESU or Harris & Bruno coater, that’s Gravure in action.

History teaches us a great deal when we apply the lessons learned to our current lives. Few bother to take advantage of the numerous mistakes our forefathers made. If we did, we would see how history is often repeated. With today’s amazing progress of digital devices, we must determine what platform will ultimately prevail and use caution when assuming nothing can ever defeat the status quo. Meanwhile, if anyone has a Direct-Lithography press available, I want one for the museum!

Nick Howard, a partner in Howard Graphic Equipment and Howard Iron Works, is a printing historian, consultant and Certified Appraiser of capital equipment. nick@howardgraphicequipment.com.

This article was originally published in the January/February 2021 issue of PrintAction.

Print this page