Features

Chronicle

Opinion

Tripping over the obvious

The role of print in modernizing society

October 7, 2021 By Nick Howard

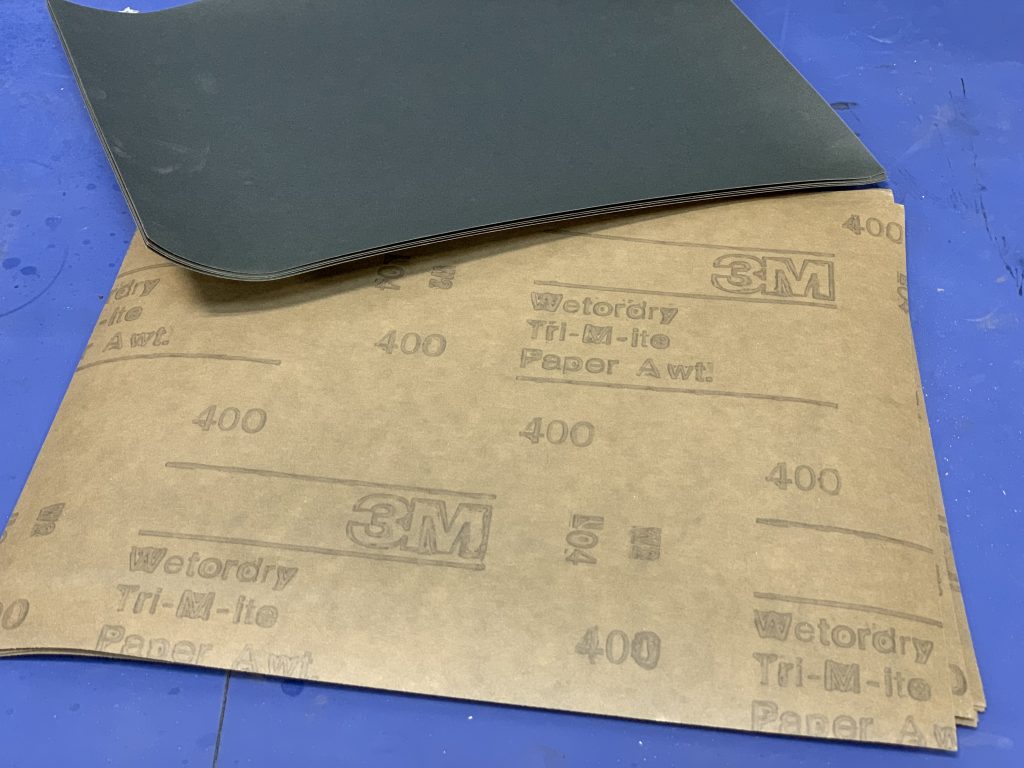

Ink producer Francis E. Okie played a major role in the invention of the Wetordry sandpaper. Photos courtesy Nick Howard

Ink producer Francis E. Okie played a major role in the invention of the Wetordry sandpaper. Photos courtesy Nick Howard Printing industry annals are filled with tales of major inventions benefiting all of mankind. For instance, take the story of Francis E. Okie. Born in 1880 in Delaware County, Pa., Okie entered the printing ink business in the 19th century. He owned a shop at 124 Kenton Street in Philadelphia. At first, the F.E. Okie Co. specialized in lamp-black inks. These inks derived their black pigments from the burning soot of mineral oils. The pigments were slow to produce, and the messy soot created a filthy environment.

Unhealthy conditions

After the First World War, there was fierce competition and slim profits in the ink business. Okie’s ink company wasn’t an exception. A company in the business of beveling glass for mirrors and tables shared space with Okie. Grinding and sanding glass meant the shop was always encapsulated in a massive cloud of dust. On one visit, Okie learned the owner wanted to sell out, probably due to the unhealthy working conditions. That’s when a lightning bolt of an idea struck Okie. Why couldn’t these dry-grinding materials of garnet and flint be made waterproof and used in combination with a liquid to keep down the grinding dust? Why, indeed!

Okie started to experiment with waterproof adhesives that could be applied to a paper with a sprinkling of garnet laid onto the sticky surface. Garnet proved a poor abrasive and the right glue formulation was elusive, but Okie soldiered on, experimenting with a variety of materials until one day he went searching for a better supplier of grit.

On a frigid January in 1920, a letter arrived at the offices of a fledgling abrasives firm in St. Paul, Minn. Established in 1902, the company was in the business of mining and selling all sorts of abrasives, including sandpaper. Okie had actually written to the Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Company (3M) to enquire if he could receive samples of their minerals.

The breakthrough

The request intrigued 3M enough to meet Okie. In Philadelphia, the Minnesotans studied Okie’s breakthrough. 3M also learned Okie had received a sample batch of wet sandpaper from a 3M competitor, but they never bothered to ask why he wanted it. In 1921, a deal was struck between the two, and 3M would soon have its second major product, now with its own brand: “Wetordry”. This was a perfect fit for 3M as they were already supplying flint, emery and garnet papers. Wetordry would take the world by storm. Every automotive body shop and metal polisher jumped at the chance to use a waterproof paper that didn’t clog and reduced dangerous dust in the workplace.

The rich history of 3M was built on an off-chance letter from an ink manufacturer. As a result, 3M would earn billions of dollars. Decided his invention offered higher rewards than blending lamp-black inks, Okie closed his business and moved to 3M’s headquarters in Minnesota. He worked at 3M until retiring in 1930 to devote himself to writing religious poetry. He lived a long life, passing away in 1975 at the age of 95.

Had Okie not had the glassworks next door, who knows if 3M would have had the opportunity to build on Okie’s innovation with thousands of more inventions—many in the graphic arts—and become a symbol of American ingenuity?

Today, 3M is a USD32-billion business manufacturing 60,000 products worldwide. Okie, the ink- maker in Philadelphia with creepy ads, has left his indelible stamp on 3M’s success.

Nick Howard, a partner in Howard Graphic Equipment and Howard Iron Works, is a printing historian, consultant and Certified Appraiser of capital equipment. He can be reached at nick@howardgraphicequipment.com.

This article originally appeared in the October 2021 issue of PrintAction.

Print this page