Features

Chronicle

Opinion

Alva and his newspaper

One of the brightest minds of the modern era began his work life as a printer

April 25, 2022 By Nick Howard

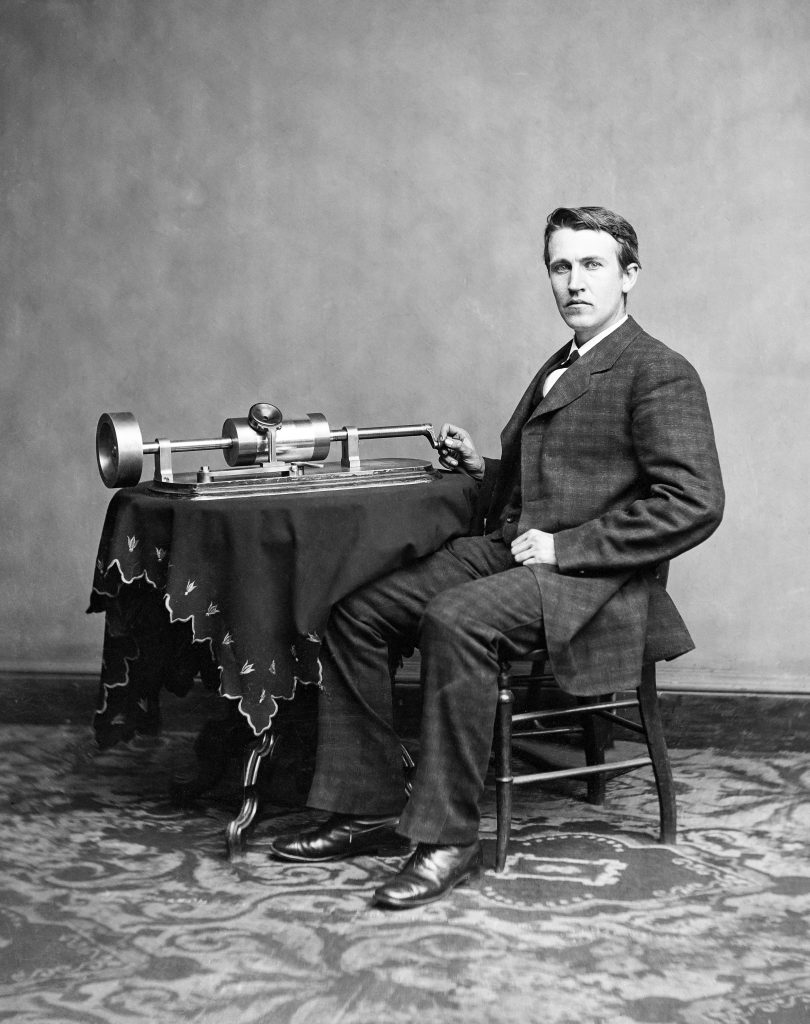

Thomas Alva Edison. Photo © Caifas / Adobe Stock

Thomas Alva Edison. Photo © Caifas / Adobe Stock In 1859, a leg of the Grand Trunk Railway ran between the cities of Port Huron and Detroit, Mich. Onboard an old springless boxcar, 12-year-old Alva set up his small shop to print The Weekly Herald newspaper. The paper sold for three cents a copy. Alva was an inquisitive lad, and had been homeschooled by his mother in Port Huron.

His father was born in Nova Scotia. He later relocated to the village of Vienna in southwestern Ontario. In 1837, Alva’s father was embroiled in the Upper Canada Rebellion and was forced to flee to Ohio in the United States, where Alva was born.

As a child, Alva became fascinated with the world of science and would spend countless hours preparing various chemical experiments at home. An incessant need for money to support his expensive hobby drew him into the world of printing. Alva reckoned that a newspaper with space for people who rode or worked on the railroad to advertise in had the makings of a lucrative business. Even by late 19th-century standards, his equipment was rather sparse. Three hundred pounds of used lead type was soon purchased from the Detroit Free Press while a crude hand-crank proof press, capable of printing a 12 x 16-in. sheet, was scrounged along with inks, a type stick, and paper. The whole shop fit into a corner of an old boxcar that was once used as a smoking compartment.

Getting started wasn’t easy. Alva cut a deal with the railway company. After composing the paper, he’d be kept busy printing the couple-of-hundred papers while bouncing along the railway track to and from Port Huron and Detroit. Stories of the people who worked in the railway found themselves in print along with small advertisements, timetables, and gossip. One such ad offered “office copying presses,” an early and only way to make copies from a typographic form. At such a young age, Alva often added his own “Op-ed” philosophy: “Reason, justice, and equity never had weight enough on the face of the earth to govern the councils of men.”

Even though he was busy, Alva found time to conduct chemical experiments. One day, a bottle of phosphorus, one of the many ingredients that had accumulated in his shop, fell down. The acid quickly set the boxcar on fire. Thankfully, the conductor saw the smoke and managed to put out the fire. However, he tossed all of Alva’s print shop materials and chemicals out of the train in anger. He also gave Alva a good thrashing, which included boxing his ears, before forcing him out of the train. It has been suggested the beating may have resulted in lifelong deafness.

Reports indicate that after his rapid expulsion, Alva drudged back along the tracks to search for, and retrieve, his possessions; including all of the eight- and 12-point types used to print the Herald. Despite this setback, the paper continued.

By the age of 13, Alva was said to be earning $50-per week ($1,700 in today’s money) from his paper, in addition to sales of everything from candy to vegetables. In contrast, at 12, I was too busy watching Heckle & Jeckl cartoons and getting into mischief. Serendipity would intervene soon.

In 1862, Alva saved the life of a toddler whose father was a station agent in the railway office of Mount Clemens, Mich. Grateful to Alva, the child’s father offered to train him as a telegraph operator. Alva soon found himself out of the newspaper business and holding a new position in the telegraph office of the Grand Trunk Railway in Stratford, Ont.

The telegraph was revolutionizing communication, and by the age of 19, Alva was working for Western Union in Louisville, Ky.

Although captivated with Samuel Morse’s telegraph, he continued with his chemical experiments until the day a bottle of sulfuric acid spilled onto the floor. The liquid wicked through the floorboards onto his boss’s desk below. This resulted in another quick dismissal.

Perhaps no one could have anticipated what was in store for this young man who simply couldn’t stop experimenting. Alva then moved to New York City. A parade of inventions began hatching in his lab in Menlo Park, N.J.

He would soon be recognized as one of the world’s greatest inventors, credited with discovering the light bulb, phonograph, and power generation technologies that have reshaped early 20th century. I’m sure you’ve guessed by now that I’ve been talking about Thomas Alva Edison, “the Wizard of Menlo Park,” a boy genius with minimal homeschooling and a constant desire to discover something new.

How ironic that just a few years after Edison left Stratford, another inventor, Alexander Graham Bell, would make the first telephone call in the town of Brantford (Ont.), which was only an hour away?

It is worth remembering Edison began his professional journey as a printer. Who said the best and brightest minds don’t have ink in their blood?

Nick Howard is a partner in Howard Graphic Equipment and Howard Iron Works. He is a printing historian, consultant and Certified Appraiser of capital equipment. Contact him at nick@howardgraphicequipment.com.

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2022 issue of PrintAction.

Print this page