Features

Chronicle

Opinion

Something new for 33

The pioneering design of Harris LSB

October 28, 2022 By Nick Howard

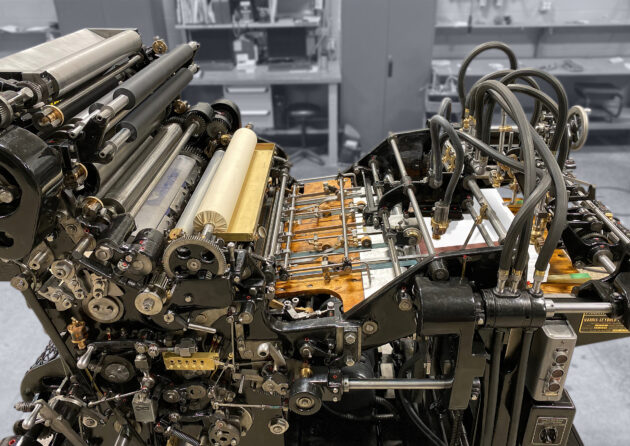

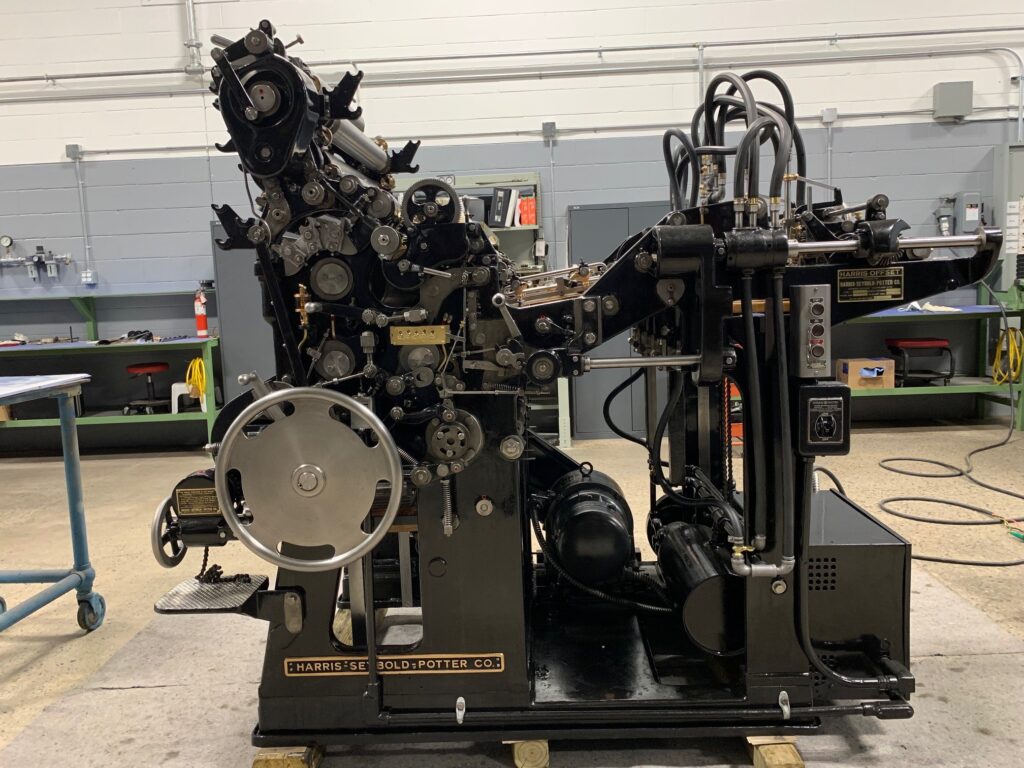

The Harris LSB after restoration by Howard Iron Works. Photos courtesy Nick Howard

The Harris LSB after restoration by Howard Iron Works. Photos courtesy Nick Howard The rusty hulk was parked inside a glass foyer of what was once home to Toronto’s graphic arts training school. The days of company-supported union educational programs are a distant memory, and this Harris LSB had to make room for new tenants. The little press had lost whatever appeal it may have had and was just 4,750 lb of obsolete machinery. Our museum (Howard Iron Works) wanted to save and restore the famous press that was made by an enterprising company during the height of the Great Depression.

The museum LSB was built in 1935, but the first models appeared in 1933. With a maximum sheet size of 17.5 x 22.5 in., this would be Harris’s first attempt at entering the then rapidly growing small format offset business. As today, printers sought affordable methods of printing. Letterpress was the dominant technology then but offset offered better quality and colour, and faster speeds. Today, digital manifestations are doing the exact same thing to win over traditional offset users. Even during the Great Depression printers were game to try new things.

There were few challengers when the Harris LSB first came out. In England, Crabtree had built a small press. In America, Webendorfer with the Chief offered the only local competition. This shows that offset builders spent most of their resources on larger machines. In the end, Harris built just 646 LSBs between 1933 and 1943. In 1945, the model was superseded by the LTG.

Reviving an old press

Restoration was a slow and painstaking process of re-learning and demystifying an assemblage of crude mechanical levers, cams and, often laughable by today’s standards, mechanics. Our goal was to print a job on this press, which we achieved after months of work. A copy of a Harris 1935 advertisement was recreated and produced with a sheet size of 14 x 20 in. The normal problems and shortcomings faced by operators in the Thirties were clear to us, as we had to re-learn to “copperize” the steel oscillation rollers: a long-forgotten process, which if not carried out properly, would cause such bad ink stripping that printing was impossible. Then there was the sheet feeder. Unlike a modern centre separation, the old Harris-HTB feeder was clunky, used “combers” to crack the pile, and offered few precise adjustments. For register, the LSB didn’t have the “feed roll” infeed but rather “tumbler grippers” and front stops, timed to a “push” side guide. To maintain any sense of register the feedtable wheels had to be set perfectly, and this was a big problem even in 1935.

The most important tool for a press operator was an oil can, not a quarter-inch spanner. The complete press was built without a single anti-friction (ball or roller) bearing. All moving parts were running in bronze or simple cast iron bearings. As typical of the times, the machine had to be oiled by hand and at daily regular intervals. To forget was a sin and a seized part would often manifest itself at an inopportune time. In short, operating an LSB was a frustratingly difficult task, and producing quality print was an even bigger undertaking.

When it was time to go home every roller had to be removed and cleaned by hand: there was no wash-up attachment for the little press. This meant that the next day rollers had to be replaced before inking up. The molleton (cloth) dampening tray had to be filled with a water bottle as Baldwin auto-feed jugs were only starting to be installed on larger models. Too much or too little dampening solution was typical and letterpress printers had a hard time learning the mystery of water and ink balance. Our print job ran well considering we had spent plenty of hours cursing the little press!

On the battlefield

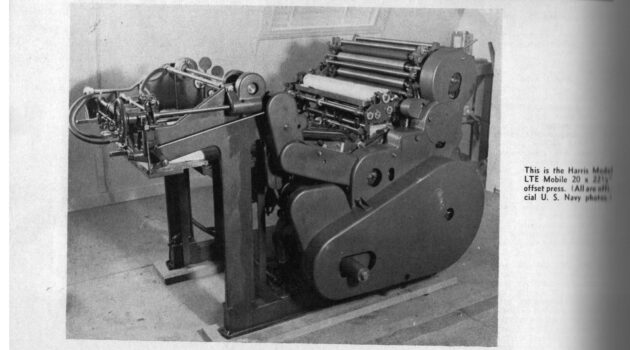

Besides being the innovator of small format offsets, the little LSB had another important role to play. In 1941, once America entered the Second World War, the LSB was used on battleships, destroyers, and Quonset hut ground installations around the world. The U.S. defence forces requested Harris, who had by that time stopped building printing machines in favour of gun-mounts, to produce a lightweight press in the 20 x 22.5 in. sheet size. The armed forces needed a press that could easily be moved, operated on the back of a truck or in the field, and possess a print quality sharp enough to reproduce reconnaissance photographs. While larger presses were utilising the offset process to print cartographic maps, the idea of mobile print shops close to the action was relatively new.

The British had already been doing this with Crabtree presses. Germans also built mobile units with Roland (now Manroland) presses. The Americans had tried using Webendorfers and Multiliths but neither press was ideal. Harris went to work and lobbed off over 1,000 lb while re-engineering the LSB into a special military press known as the LTE.

We are unsure how many LTEs were made by Harris as those records are still classified, but we can safely say there were at least 100. Most of them were used in the Pacific area. Perhaps this explains why the only LTE known to exist is at the China Printing Museum in Beijing. The press, painted an ugly green, caught my eye when I visited the museum a few years ago. It stands 5-ft tall and gives a rare glimpse into the importance of print to the war effort. Meanwhile, our restored Harris LSB is in full bloom at Howard Iron Works awaiting those who missed its heyday over 87 years ago!

Nick Howard, a partner in Howard Graphic Equipment and Howard Iron Works, is a printing historian, consultant, and Certified Appraiser of capital equipment. He can be reached at nick@howardgraphic.com.

An edited version of this article originally appeared in the September/October 2022 issue of PrintAction.

Print this page